As a female entering her teenage years, I was given plenty of advice about how to choose “Mr. Right”.

“Find a man who respects you!”

“It’s important to have a man who can make you laugh.”

“Make sure the man you choose can support you!”

Though well meaning, some of this advice – from family, friends, or acquaintances – contained underlying assumptions about my life goals and expectations for myself. The last piece of advice, for example, is one that I heard many variations of throughout my preteen and teen years. My family in particular, wanted to be sure I would have a husband that could provide for me and take care of me when I was no longer under their care. This advice, of course, stemmed only out of love for me. Yet, finding a man that could support me – in other words, a doctor or engineer or scientist with a hefty salary – implied that, without a man, I would be unable to support myself. I needed a man – to provide for me and to protect me from the big, scary “real world”.

Men experience a variation of this same bias. Familial and societal pressures can help instill in them the unconscious belief that they need to be those providers – if they want a woman, they are going to have to be able to make the money that she can use to get her nails done and buy her shoes. In order to do that, they need the hefty salary that comes with being a doctor or an engineer or a scientist. In short, it’s his responsibility to “bring home the bacon”. These expectations for men and women – perpetuated by families, by peers, and by society in general – may play a large role in the differences we see between men and women in later performance, behavior, and career choices. For this reason, familial and societal expectations may be at least partly responsible for the gender gap we currently see in science, engineering, and math fields.

Parental and Societal Expectations

One the reasons that familial and societal expectations for children may have such a profound effect on their later development is that these outside expectations influence the expectations that children have for themselves. In her essay “Do Sex Differences in Cognition Cause the Shortage of Women in Science?”, Melissa Hines confirms that “parental expectations have been found to influence the expectations of their children”. Other research has also found that parental expectations for what children will achieve had a “moderate to strong” influence on the children’s own goals (“Parental Expectations”, 2). So, if a child grows up in an environment where he or she is expected to pursue higher education, a degree in STEM, or even a specific career (a doctor, for example), they are likely to adopt similar goals for themselves.

Societal influences also play into the types of expectations that children form for themselves. From young ages, girls are exposed to media that depict “perfect mothers”. These girls may feel pressure to tend to the housework, cook the meals, care for the children, and other stereotypically “female” roles as a result of these influences. In academia, certain subjects may also be seen as stereotypically “male” or “female”. Gender-science stereotyping can influence the decision of males and females, positively or negatively, to pursue a career in STEM (Smyth, 2).

We have seen that parental and societal influences can influence the expectations that children develop for themselves. It follows that these self-expectations are crucially important to future academic and career outcomes. In her essay, Hines explains that expectations and beliefs have measureable influences on the brain and behavior, which have been linked to performances in subjects such as mathematics. As Hines eloquently expresses, it is truly a self-fulfilling prophecy; the expectations that parents have for their children can significantly impact whether a not a child will fulfill those expectations (Hines, 110).

Of course, when we discuss expectations and the role they play in children’s future success, we must acknowledge that the trends discussed are in no way absolute. Simply because a parent expects that his or her child will receive higher education does not ensure that they well – it merely increases the likelihood. This could be due to a variety of factors – the parent exposes his or her child to more educational opportunities during childhood, for example, or perhaps discusses higher education options during adolescence. There also may be a genetic factor; children of college graduates may be more intellectually capable of receiving a college degree, and are therefore expected to do so. Regardless of the reason, there is a clear link between expectations and future behavior that cannot be ignored, particularly in the STEM gender gap debate.

Expectations and the Gender Gap in STEM

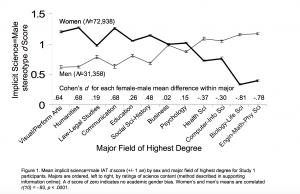

As we have discussed, there are certainly differences in expectations between men and women, in both domestic and professional spheres. The figure below is a good illustration of how certain majors are viewed as stereotypically male or stereotypically female areas of study. These stereotypes could be also considered “society’s expectations” for males and females in the realm of academia. As Hines has established, outside expectations can have significant effects on future behavioral and professional outcomes (Hines, 110). Therefore, it is possible to say that gender stereotypes about certain fields may be an important factor in explaining the current gender gap in STEM.

There are, of course, a number of other factors that could be used to explain the gender gap in science and math fields. However, the influence of parental and societal expectations is one that cannot be ignored. As I pursue my own career in the biological sciences, and also search for “Mr. Right”, I am beginning to acknowledge and discard the expectations that require me to fit a certain mold. Gender stereotypes for both genders are prevalent in families and in society today, such that we have all experienced them in one form or another. Perhaps with the rise of new wave feminism and the rejection of old gender expectations, we will see the STEM gender gap come a little bit closer to closing.

References

Hines, M. (2007). “Do sex differences in cognition cause the shortage of women in science?”. In J. Ceci & W. Williams (Eds). Why Aren’t More Women in Science? (101-112). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Smyth, F. L., Greenwald, A. G., Nosek, B. A. “Implicit gender-science stereotype outperforms math scholastic aptitude in identifying science majors”. Project Implicit. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.366.8870&rep=rep1&type=pdf

(2012). “Parental expectations for their children’s academic attainment: indicators on children and youth”. Child Trends Data Bank. http://www.childtrends.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/115_Parental_Expectations.pdf