Kimberly Crenshaw is someone who I’ve studied before in WGSS classes both here at the University of Richmond and at my previous school, the University of South Carolina. We mainly went in depth about the term she coined as intersectionality in WGSS 279, Feminist and Queer Theory. The part about identity politics stood out to me in the reading. She mentions, “Ignoring difference within groups contributes to tension among groups” (Crenshaw, 1242). This reminded me of my Feminist and Queer Theory class when we discussed how early days, white middle-class female suffragists tended to exclude women who didn’t identify as similarly to them. This could include women of color who could more closely identify with men of color than their white counterparts or class differences, among others. Crenshaw states that her objective in this article is to advance the telling of that location by exploring the race and gender dimensions of violence against women of color. Their intersectionality can lead to different experiences between them and white women, white men, and even men of color. She says that the problem with identity politics is that it frequently conflates or ignores intragroup differences, with race and class being extremely big factors in this discussion. Something particularly meaningful to me, as a woman of color, is how she mentions this particular product of intersectionality. I have encountered racism and sexism, as I’m sure other women of color have, and I have also noticed, as Crenshaw states, that these experiences are not typically represented within the discourses of feminism or anti-racism. Because it is typically seen as one or the other, she says this neglects one, both, or multiple identities. I thought her example of the physical assault of women in shelters was incredibly powerful. She attributes this to the manifestation of subordination as a result of the gender and class oppression that brought them into the shelter in the first place. As many of them are victims of domestic violence, she makes a point to also point out how, on top of dealing with the results of that violence, there are initial hurdles to overcome within the shelter as well. Cultural barriers, limited access to resources, and the fear of deportation are just some of the many challenges faced by women of color, especially immigrant women of color. It is essential to note the different obstacles and varied experiences faced by immigrant women of color, as well as the disproportionately high unemployment among people of color that separates their experiences and ability to rely on support networks. Something that really stood out to me was the choice that was outlined for many undocumented women of color, in particular, this choice between remaining in a situation involving domestic violence or being deported or endangering the security of their family. Language also serves as a barrier regarding shelter and seeking help. This all goes to show how our legal system, through Congress and others, has hurt a multitude of intersectional identities by passing anti-immigration policies, among others. There is an experience unique to women of color that can separate them from other minority identities, such as men of color and white women, due to the intersection of their multiple identities and the failure to address how sexism and racism (among others) are experienced differently and simultaneously by this group. I am going to leave off with an essential quote from the reading as I believe it really sums up the whole point that Crenshaw was conveying, “Because women of color experience racism in ways not always the same as those experienced by men of color and sexism in ways not always parallel to the experiences of white women, antiracism and feminism are limited, even on their own terms” (Crenshaw, 1252).

Mapping the Margins

29

Jan

Your reflection on Kimberly Crenshaw’s work about intersectionality is insightful and relatable. You’ve pointed out how, in the past, some early advocates for women’s rights excluded those who didn’t share the same background. This exclusion still happens today, and Crenshaw’s idea of “intersectionality” helps us understand why.

Personal experiences as a woman of color highlight how racism and sexism often intersect, creating unique challenges. The example of women facing violence in shelters shows how issues like gender and class can pile up, making things even tougher. African American women face this discriminatory intersectionality in different ways every day. From the political discrimination, we faced during the antebellum period while fighting for antislavery and being excluded by white women and black men to the expectation of African American women to be independent and persevere because of the historical strength we must keep up for our safety, sanity and simply because no one else would.

You’ve also highlighted the struggles of immigrant women of color, who face difficult choices due to anti-immigration policies. Your point about language barriers and the fear of deportation adds another layer to the challenges they encounter. I would like to say that it took me aback to read that the husbands of immigrant women of color are their “links to the world outside their homes” however it was not and I would be lying. It is very clear and easy to understand how it is an easy control tactic to keep women “in their place” and easy to abuse.

The quote you emphasized, “Because women of color experience racism and sexism differently from men of color and white women, anti-racism and feminism have limitations,” summarizes Crenshaw’s main point. It underscores the need to understand that everyone’s experiences are different, and traditional approaches may not address these unique challenges effectively.

Your response shows a clear understanding of how intersectionality helps us see the complexities in people’s experiences, especially for women of color, and why it’s crucial for creating fair and effective solutions.

The section you cite offers a very useful insight. Another quote from that section of the text that I think is similarly useful, in discussions of intersectionality: “racism as experienced by people of color who are of a particular gender – male – tends to determine the parameters of antiracist strategies, just as sexism as experienced by women who are of a particular race – white – ground the women’s movement. The problem is not simply that both discourses fail women of color by not acknowledging the ‘additional’ issue of race or of patriarchy but that the discourses are often inadequate even to the discrete tasks of articulating the full dimensions of racism and sexism” (Crenshaw 1252).

Crenshaw demonstrates here that Intersectionality is not an additive theory; Black women’s experiences of oppression are not simply an experience of patriarchy in addition to one of white supremacy. The experiences of Black women with oppression have to be understood through the particular position and sets of relations that constitute Black womanhood. This is an important point, for understanding the experiences of Black women, but also for understanding the experiences of Black men and white women. It is not that Black men just experience racism, in absence of gender: the racial oppression Black men face is gendered, as Crenshaw explores in her discussion of the images of Black male sexuality. Likewise, white women do not just experience sexism, in absence of race: the gendered oppression white women face is raced. Intersectionality, as a way of understanding the particular experiences of specific social positions, reveals the ways in which these structures of oppression are mutually inseparable.

I liked how you highlighted from the reading what I thought was one of the main points; how within these different cultures or groups, there are even more sub-groups among them that experience this intersectionality that the author mentions. You note it but I also believe it’s important to go over it as well. I feel it is often overlooked just how much African American women were put up against. Considering all black people were thought of as being less, and women were thought to be second to their male counterparts. Imagine how it must’ve felt to not only be a woman but black as well in a racist and sexist society. It really puts things into perspective. I liked how you talked about obstacles because there is a part I wanted to elaborate more on. A huge obstacle was the measure of domestic violence black women are faced with. Crenshaw references a book where she states how black men use violence to assert their dominance and control over their women partner (Crenshaw, 1254). What this book did, despite reinforcing stereotypes, was also showing how black women, in times of distress, were reluctant to call the police (Crenshaw, 1257).Would you call someone to help when you know they are known for only creating more problems, sometimes ones that would get you killed.

Because of this, black men would inevitably have the power within the household. This violent patriarchy style is what’s interesting to me because black men shouldn’t have to resort to violence. I had discussions about this before in my Africana Studies course and we talked about how black men needed to gain their identity. Their culture, name, and manhood was stripped from them through slavery and now they were desperate to gain their respect once more. We talked about how they would copy their male white peers as to how to move up the social class. However, white men only showed them disrespect and violence in return. As a result, black men began to exhibit the same traits. Definitely worth looking into more, because I believe the behavior of black men correlates to their search for identity.

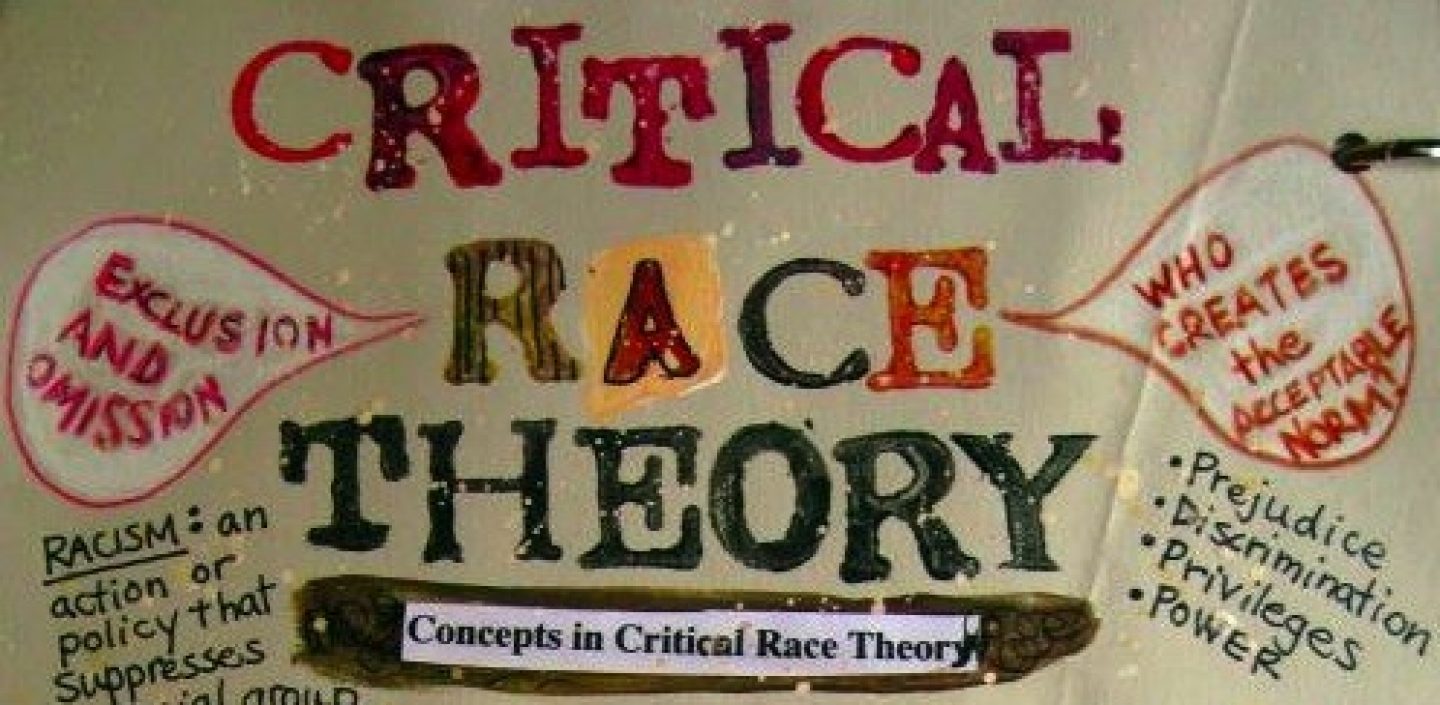

I like how you mentioned Crenshaw’s coined term, Intersectionality, as it provides a lens on how Identity politics work. It is an ideology that many ‘supporters’ of different minority identities fail to consider, in terms of how Intersectionality impacts people who have an intersectional identity. When you highlighted this in your blog post, it was a point I had never considered an issue before reading this article. Initially, I believed conversations within feminist platforms equitably addressed the needs of women across the racial spectrum, regardless of the different steps it would take to get there. However, as you pointed out in this piece by Crenshaw, platforms like the Feminist movement fail to incorporate these views into their movement at the highest level, primarily because leaders in this movement do not have an Intersectional identity, and are ignorant of what role that plays in their quest for women’s rights. Crenshaw does provide examples like white women’s experiences with sexism vs black women’s experiences with sexism. Sexism is something that women of both races can experience. Still, sexism and racism compounded together is not an experience that white women have, and because white women are usually the people in power in these feminist conversations, it impacts the overall help that intersectional identifying people can receive from these platforms that are supposed to help them. This example that Crenshaw provides shows the second tenet of Critical Race Theory in effect, the structural component of racism. The current policies and people with the power to change these policies in this specific example of feminism show how those of the non-majority are not accounted for, as supported by the lack of a platform available for these intersectional identifying people.