“It’s just a bad stomach ache, right?

Wrong.

As I have been informed by many, I realized I left off on quite a cliffhanger. (Whoops!) If you don’t recall where we left off, refresh your memory with the last paragraph of Part 1. For others, let me begin building the bridge across the cliff I left you all hanging on.

Our story picks up with the undigested evil twin of gliadin heading into the small intestine. If you had a similar K-12 education as myself, you are probably of the belief that the small intestine handles nutrients for pee and the large intestine handles nutrients for poop.

To set things straight, all food goes through the small intestine first and is not just a tube for transport. It’s a highly efficient nutrient-grabbing tube decked out with an intense microbial security system.

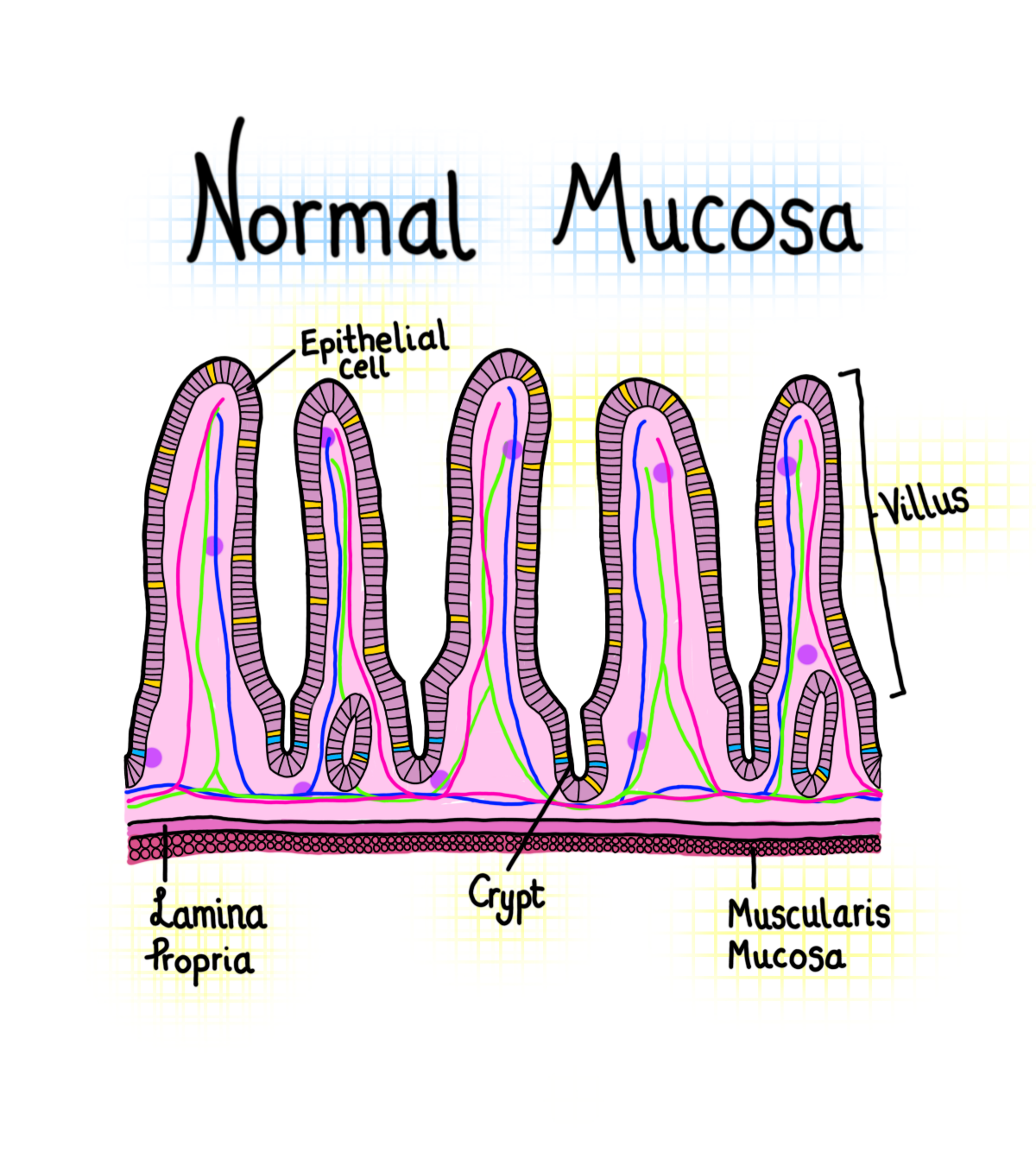

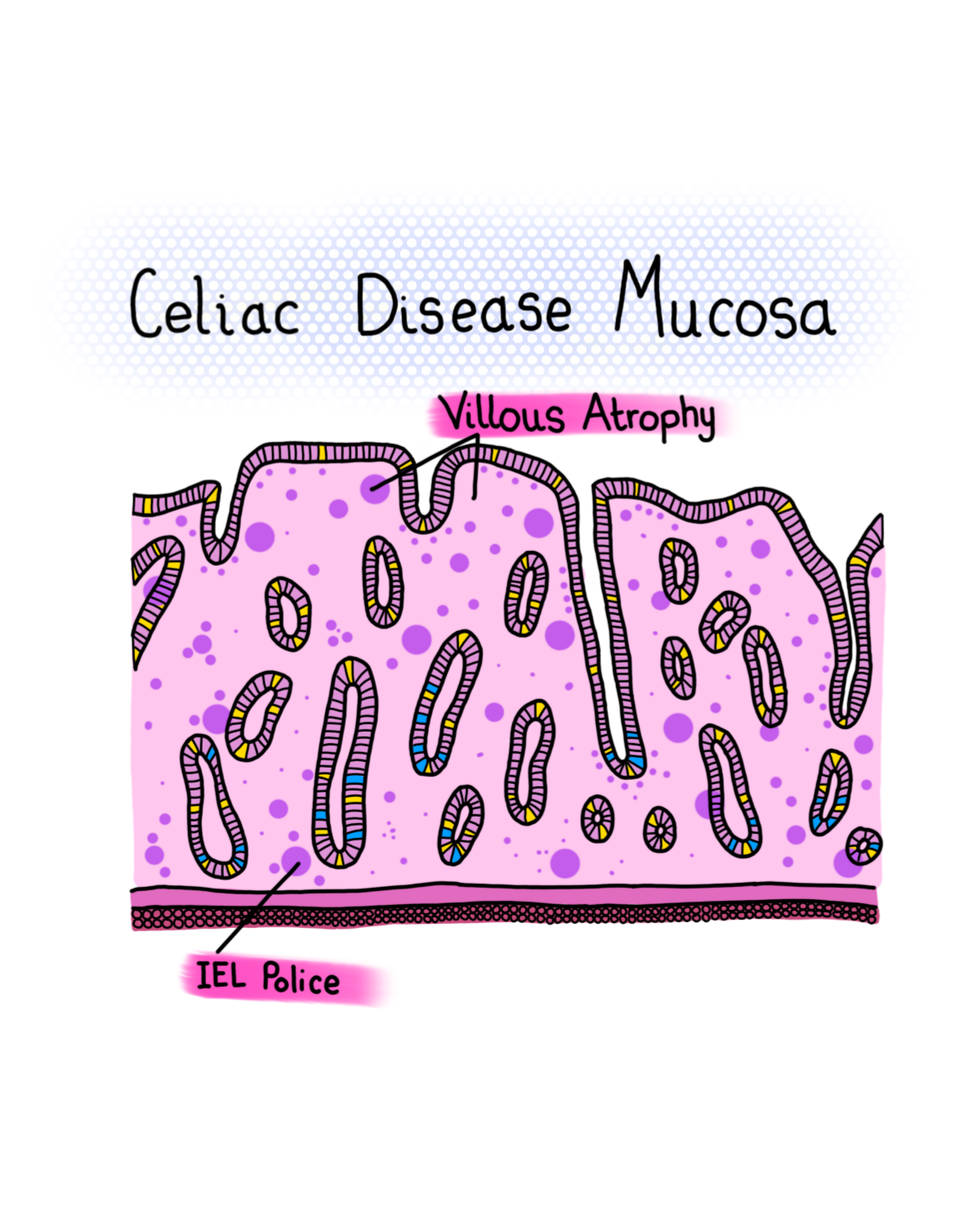

The small intestine is lined on the inside with a protective barrier, like the bark on a tree. Similar to a tree, it has branches that extend inside the intestine which aid in nutrient absorption. These finger-like branches (labelled below) are named villi and are still covered by the bark, or epithelium.

The epithelium (protective bark) is made up of aptly named, epithelial cells. These cells protect the lamina propria and mucous layers all within the that magnified section in the wall of the intestine. This system is zoomed in below.

Now that we understand the structure of the small intestine a little bit better, it’s easier to describe what happens when gliadin enters.

On its journey through the small intestine, things normally go just fine. The appropriate enzymes and nutrients are absorbed, and it continues onward toward digestion and….um…evacuation.

However, some individuals are born with an HLA-DQ2 or DQ8 gene. Aside from this being a jumbled mix of letters and numbers, cells ridden with this DQ8/2 gene notice gliadin as an intruder moreso than cells without the gene. This is why the HLADQ2 or DQ8 gene is often used in the diagnosis of celiac or signifies a predisposition to Celiac Disease.

Once the gliadin is identified by these HLA-DQ2/8 cells, it actually does not do much. Except when a game of telephone starts. The HLA-DQ2/8 cells don’t do much functionally, but they do tell their cellular friend, who tells another cellular friend, who tells another cell friend in a fashion that is not far off from middle-school telephone.

(Most immune system responses are large telephone-like signalling pathways, in their simplest form).

There is one exception to intestinal mucous layer telephone though. It does not get as messy and the simple message is communicated very clearly down the cell pathway.

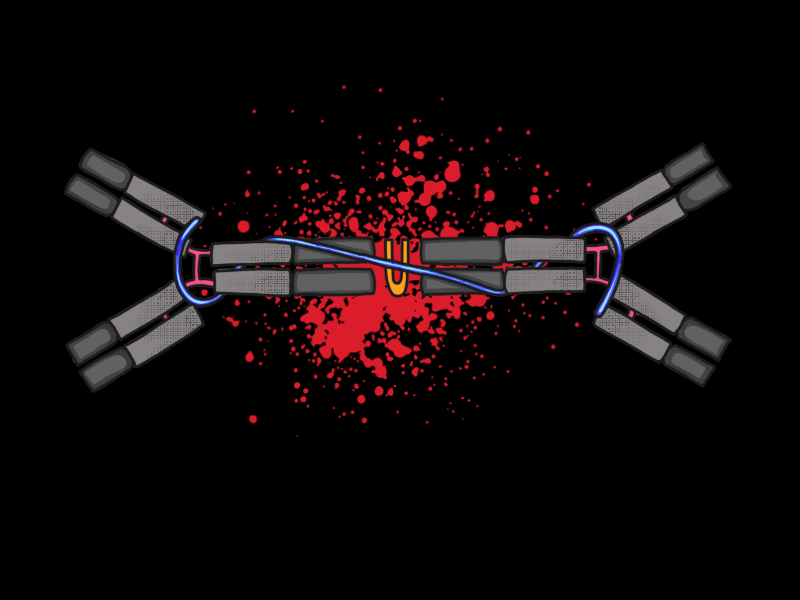

By the time the intestinal immune system telephone finishes, the message reaches the IgA antibodies (pictured above). You may recall from 10th grade science that an antibody is created by the immune system and functions to stop intruders from harming the body. In this case, the gluten.

But gluten is not supposed to be a harmful intruder! It was that silly gene mutation that rang the alarm bell! Exactly, but after a rapid and precise game of telephone, the mistaken “intruder” has already set off a large immune response. Actually, multiple.

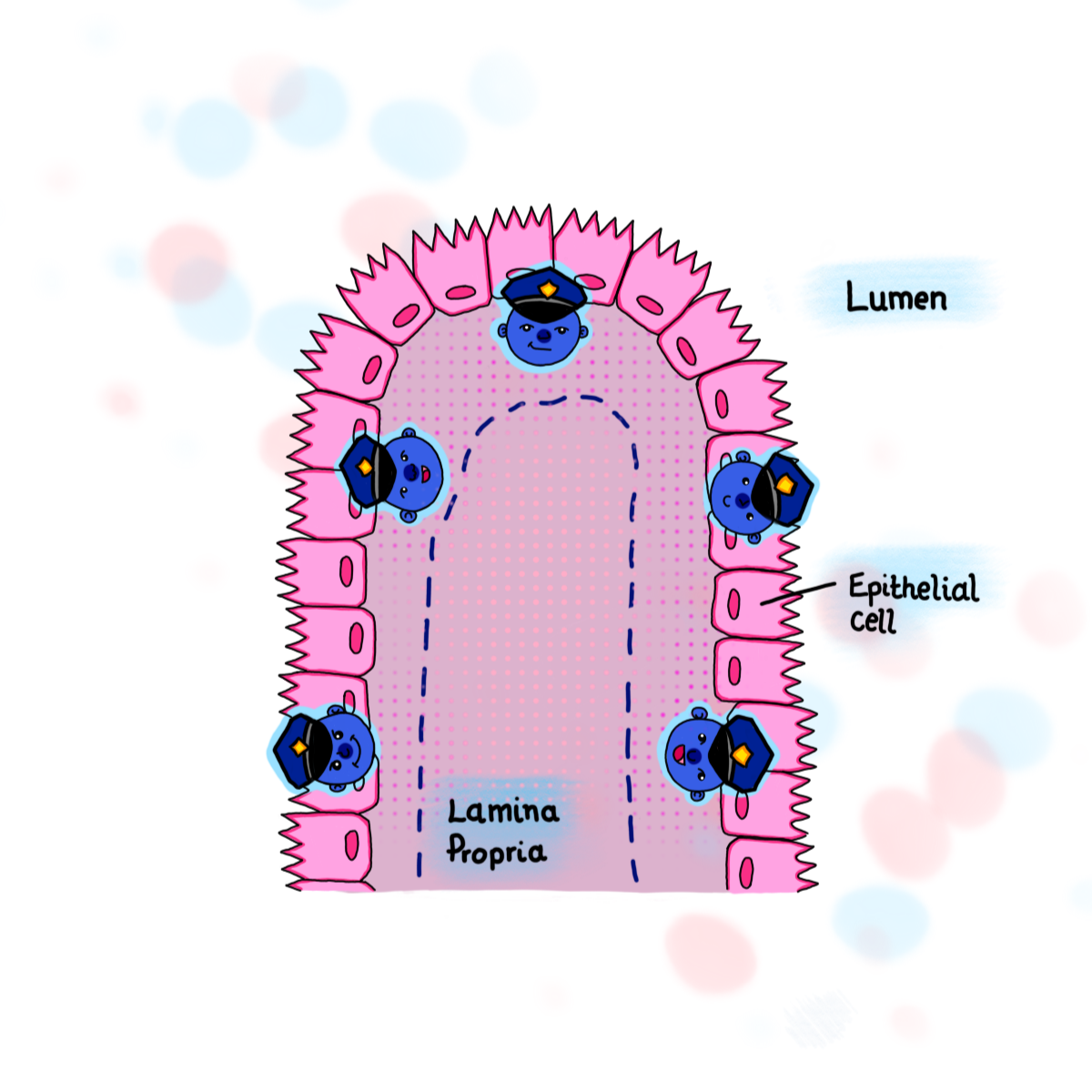

Remember when the HLA-DQ2 made it’s silly mistake and gossiped to a friend that told the other friend that then told IgA, and IgA got prepped to search and destroy. Well, this macrophage also talks to a whole different group of friends that work to raise intraepithelial lymphocyte (IEL) production.

I could break down this word, but I find it better that you think of this cell as a policeman. In fact, many researchers do too!

(Don’t believe me, check the title of Reference #9)

Similar to the vengeful IgA, these policemen try to control chaos in the intestine and mucosa. Yet similar to real policemen, when the problem (gluten) keeps returning, the immune system continues to send more and more enforcements of IEL cells to the same spot.

This reaction leads to the pictures you see below. The high IEL count, abnormal increase in IgA, and swollen villi branches (villous atrophy) are critical biological markers for Celiac diagnosis.

Overall, the mucosa is quite damaged from just a crouton’s worth of gluten ingestion. This is why Celiac Disease needs a gluten free diet.

The active immune responses that occur in the gut can often extend towards other organs and tissues, not remaining an isolated event. Individuals with celiac often have abnormal liver biochemistry, anemia, arthritis, and multiple other non-intestinal conditions.

The dietary restriction for Celiac Disease is far from a choice and one of the only effective therapies for this immuno-compromised condition.

You may be wondering about the 20% of people who are gluten intolerant or eating gluten free without Celiac Disease. Does their intestine balloon similarly?

The short answer is: No, not quite. And the long answer is Part 3, coming soon.

Art and images for this article created by Molly Yon Hin.