Identify is a monthly series here on the SAL blog, focusing on students, faculty, and alumni of University of Richmond who have used GIS in exciting ways. Come by each month to learn more about the interdisciplinary nature of GIS here at UR.

Megan Sebasky ’10 (l) and Dr. Carrie Wu (r) at the Evolution 2010 meeting presenting their ecological niche modeling research.

The University of Richmond prides itself on offering plenty of opportunities for undergraduate students to perform rigorous research alongside one of the University’s excellent faculty members, many of whom are experts in their fields. Often, these undergraduate research experiences help students determine their future endeavors and offer them a chance to have their name on published material soon after college. Megan Sebasky ’10 not only took advantage of undergraduate research by working with Dr. Carrie Wu, Assistant Professor of Biology, but also used her GIS expertise to further the value of her research.

Sebasky majored in biology and environmental studies; while a rising senior, she joined the lab of Wu, who had recently been hired at the University of Richmond after working at Duke University. At the time, Wu was working on research focusing on the plant species Mimulus tilingii, commonly referred to as the mountain monkey-flower. Sebasky mentioned she had GIS experience, thanks to the classes she took here in the Spatial Analysis Lab, which immediately attracted Wu’s attention: Wu’s research about the mountain monkey-flower contained a strong geographic component, one which would immensely benefit from GIS.

In particular, prior research had indicated that there may be two separate sub-species of Mimulus tilingii, one located primarily in Oregon and Washington, and another found further south in California. One approach Wu had identified to test whether there were actually two species involved ecological niche modeling, or using spatial information about environmental variables to determine the exact ecological conditions a species needs to thrive. If Wu and Sebasky were able to determine that the two presumed sub-species required different environmental conditions, they would have strong evidence to conclude that these sub-species were indeed taxonomically different.

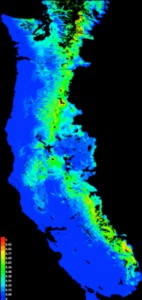

An output map from MaxEnt, showing the predicted occurrences for the mountain monkey-flower as a whole.

Sebasky conducted her side of the research by using ArcGIS as well as software called MaxEnt, which is among the most popular pieces of software for ecological niche modeling. Using the heat maps produced by MaxEnt, Sebasky and Wu determined that not only was the mountain monkey-flower ecologically divergent from its nearest relative, but that there were two distinct groups whose ranges split near the California / Oregon border. In addition, they found that cold temperatures were especially important for delimiting the ranges of the two sub-species. Armed with this new knowledge, they traveled in 2010 to the Society for the Study of Evolution’s annual meeting, which was held that year in Portland, Oregon, to present their findings. A full write-up of the research is forthcoming.

This success would not have been possible without Sebasky’s experience in GIS. While Wu was familiar with GIS, she admits to learning a lot more from Sebasky; since then, Wu has encouraged other students to pursue research projects with GIS components and to take the GIS classes offered at the University of Richmond. “Even when I go to professional meetings [for biology],” Wu says, “[GIS] is coming up more and more. … It’s not just one little corner anymore.” And like any good academic, Wu hopes to continue to learn more about GIS as she continues throughout her research career.

As for Sebasky, the great experience she had with her undergraduate research led to her present educational endeavors. Currently a Master’s student at the University of Virginia, Sebasky is continuing to work on GIS-informed ecological niche modeling, looking at an invasive species from Europe now found in the United States. Says Sebasky, “In grad school, I have found that ecological niche modeling has become extremely popular in the literature and being able to do it is an extremely helpful skill set to have. I have been doing a lot of networking at conferences … and people are really interested in what I’m doing.”

Here at the SAL, we are glad to see our alumni achieve these great accomplishments and know that the strong GIS foundations they received as undergraduate students help them to reach these outcomes. And we will continue to support our phenomenal faculty in Biology, and indeed all the academic departments, as they find ways to enhance their research with GIS!