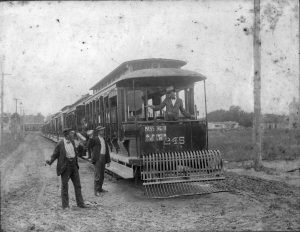

On the evening of April 19th, 1904, at least 600 Black Richmonders gathered for a rally to discuss a plan of resistance. The Times Dispatch printed the headline, “Separate the Races,” on April 17, 1904, highlighting the watershed law to which these folks were responding. A new Virginia law effectively allowed segregation on public transportation and in turn, catalyzed a pre-Martin Luther King movement of non-violent, civil disobedience in the form of a mass boycott of streetcars in Richmond, Virginia. This movement, and others like it that occurred across the nation, have since been erased from our collective popular memory. To many Americans, Black people were brought here in the 17th century to be enslaved, Lincoln gave them their freedom with the Emancipation Proclamation, then the Civil Rights movement happened in the Sixties, and finally, Obama was elected about fifty years following.

However, dissent is as much a part of the Black American tradition as call and response or signifying. This streetcar boycott is a lens through which we can deconstruct the misconception that the fight for civil rights is limited to Martin’s dream or Rosa’s refusal to give up her seat on a bus. Black resistance involved many more actors, a longer timeline, and a rich history of local protest.. April of 1904 in Richmond, Virginia serves as one starting place to recreate this more holistic narrative of both black resistance and protests in Richmond.

The first law mandating segregation on public transportation was passed in 1891 in Georgia, however it left the ultimate discretion to the streetcar company. In the wake of Georgia’s law, cities started to pass their own laws to go along with state ordinances.

In turn-of-the-twentieth century Richmond, Black people and white people hadn’t naturally segregated themselves. People often just sat where they desired before Jim Crow segregation ordinances came to be. Because of this, many Black people were shocked and dismayed by a new effort to restrict their movements, and “Separate the Races,” after years of coexisting, however uneasily. According to John Mitchell Jr., editor of the Richmond Planet, and the key leader of the boycott, this new call for segregation represented a new Richmond to which he was not accustomed. He went on to claim that since the end of the Civil War, this ordinance had sparked a “bitter feeling of racial antagonism” more than any other act had done before.

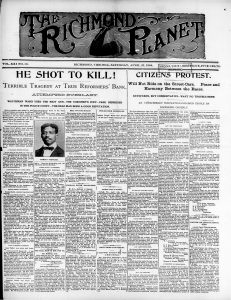

Instead of simply accepting these new changes, black leaders across Richmond decided that it was time to organize. When Mitchell invited the most prominent, yet mostly conservative, Black people in the city for a meeting to discuss a possible protest, close to two hundred people showed up. By April 19th, the conversation had grown to over 600. Four days later, The Planet ran the headline, “Citizens Protest,” officially declaring the mass boycott.

Beyond the general injustice of mandated segregation, Black Richmonders also objected that the discretion of segregation on these streetcars was left to conductors. The St. Luke Herald, run by Maggie Lena Walker, the first woman president of a bank, also reported on this meeting. One article claimed, “the very dangerous power placed in the hands of hot headed and domineering young white men. . .would certainly provoke trouble.” Fear of unqualified white men having too much power also animated the boycott.

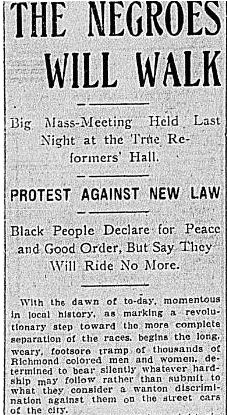

Because of the many different aspects of this issue, and the complex dynamics within the black community, it makes sense that there were many different tactics in combatting this unjust legislation. Many different responses were offered, including not protesting at all. An alternative tactic of resistance included bank leaders who agreed to join together to financially support an all Black transit system, not in the name of competition but in the name of preserving peace between the white and Black communities. Although this Black transit system never came to fruition, Black Richmonders did participate by deciding to walk and remaining steadfast in their efforts— so much so that The Planet reported that there was a high need for fish salt and witch hazel since so many people had to soak their feet. Although the success and duration of the boycott has been disputed, on May 14th, 1904, The Planet reported that 80 to 90 percent of Richmond’s Black population were walking.

This movement was deliberately relatively conservative. When he described the meeting called to discuss action against the segregation mandate, John Mitchell Jr. noted, ” it was the opinion of the body that the colored people should do all in their power to promote peace and avoid any clash or disorder on the streetcars.” The Richmond Times-Dispatch later reported on the April 19th meeting: “There was no turbulence, no fierce denunciation and no fire-eating, as many had feared. On the contrary, conservatism was urged….” Mitchell and other leaders insisted on peaceful protest. They invoked respectability politics as the best route through which to achieve their goal. Mitchell said he warned protestors not to be provoked into violence. When Black folks rode the streetcars, they were to follow the law but overall, they were urged to avoid them altogether. Despite their efforts, the protest was seen by many as a failure since Virginia voted to implement statewide, mandatory streetcar segregation in 1906.

Although conservatism and respectability are often looked down upon today, it’s crucial not to miss the inherent radical nature of this movement. Between 1904 and 1905, 133 Black people were lynched, including four in Virginia. The consequences of existing while Black, let alone protesting while Black were monumental.

Although conservatism and respectability are often looked down upon today, it’s crucial not to miss the inherent radical nature of this movement. Between 1904 and 1905, 133 Black people were lynched, including four in Virginia. The consequences of existing while Black, let alone protesting while Black were monumental.

With this, one can see that the tradition of nonviolent civil disobedience neither began or ended with Martin Luther King Jr. Instead, Black folks have been organizing and fighting for their liberation ever since they got to this country. The story of the Richmond Streetcar boycott may not have ended segregation on public transportation, but it still deserves its place in the history of Black American dissent and in the wider history of protests that have occurred in Richmond.

For too long, in popular memory, the Black experience has been whitewashed or reduced to simple, easily digestible narratives of progress. For too long, the history of “progress” in the Black narrative has both lacked nuance and inclusivity of experiences across identifiers like gender and socio-economic status. However, the Black experience hasn’t been simple and progress, whatever that means, certainly has not been linear. When we forget movements like the streetcar boycotts that swept the nation, we forget the long standing tradition of Black resistance is not relegated to the Civil Rights Movement or even to #BlackLivesMatter. To remember that Black resistance is enduring is to acknowledge both how far we’ve come and how far we have to go. As John Mitchell Jr. declared, (Black folks) “shall protest and protest. We shall agitate and agitate. We shall never willingly submit.”

For Further Reading:

Blair Murphy Kelley. Right to Ride: Streetcar Boycotts and African American Citizenship in the Era of Plessy v. Ferguson. University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

Leon F. Litwack. Trouble in Mind: Black Southerners in Jim Crow. Vintage Books, 1999.

“Stay off the Cars”- The Boycott of the Virginia Passenger and Power Company.

Susan D. Carle. Defining the Struggle: National Organizing for Racial Justice, 1880-1915. Oxford University Press, 2013.