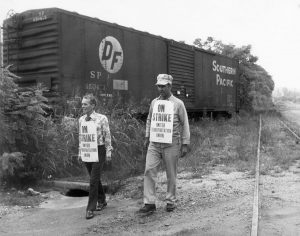

In July 1971, Richmond became a target of the United Transportation Union’s national railroad strike. The strike began at 6am on July 16th and lasted eighteen days, officially ending at noon on August 3rd. Organized by the United Transportation Union (UTU), participants objected to changing railroad policies, which would result in longer runs, the removal of opportunities for additional pay, increased layoffs, and possible relocation requirements. During the strike, the UTU employed a newly gained tactical maneuver made possible by a recent court ruling allowing for intermittent strikes with national objectives. With this new capability, the UTU targeted four railroads: the Southern Railroad, the Union Pacific, Norfolk & Western, and the Southern Pacific.

During the course of the work stoppages, The Richmond Times-Dispatch covered the strike on a daily basis. The paper of record in a town dominated by corporate tobacco firms, the RTD’s coverage reflected the point of view of its leading white elite. The paper’s coverage pitted individual rail workers against the rest of Richmond’s citizens. A close reading of the coverage of this national demonstration illustrates the RTD’s anti-union sentiments, which manifested in its significant coverage of companies’ lost profits, the possible deprivation of food and necessities, and the aim to create conflict between Richmonders and the strikers.

After World War II, the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) organized a movement, called Operation Dixie, aimed at organizing labor in the South and challenging big businesses, which had opposed the New Deal. In 1947 the Taft Hartley Act was enacted by Congress and Right to Work laws were adopted shortly thereafter by Virginia, driving union membership down and diminishing the organizational power of unions. The failure of Operation Dixie, stemming from the political divisions created by the Cold War, and the passing of Taft-Hartley could be seen in union membership rates: only 16.7 percent of Virginia’s workforce belonged to a union in 1970, compared to 32.9 percent in the heavily unionized state of New York.

After 1946, the U.S. experienced its largest wave of strikes in 1970, with 2.4 million individuals involved in far-reaching work stoppages. Union membership experienced a period of growth between 1966 and 1970 but, by 1972, it began a steady decline. During this time the labor movement was politically divided. The AFL-CIO, which had benefited from an elite position in the Democratic Party, boycotted Democratic presidential candidate George McGovern’s efforts to democratize candidate selections. They also objected to McGovern’s stance against the Vietnam War. As a result the party struggled to reconcile the needs and frustrations of the white working class with the evolving ideologies and demands for social change following the 1960s.

At the same time, the working class was being courted by the Nixon administration which, rather than focusing on the mounting economic issues, prioritized “patriotism, morality, [and] religion” as Nixon put it. Historian Jefferson Cowie has argued that Nixon’s embrace of the working class was more rhetorical than substantive: “He would make the Republican Party a bit less receptive to the needs of Wall Street and, at least rhetorically, much more open to the men of the assembly lines.” This halfhearted support of the labor movement reflects the same rhetorical vagueness exemplified by the RTD’s un-political portrayal of the UTU strike.

The Richmond Times-Dispatch’s coverage of the national strike fixated on financial loss and the spectre of consumer inflation. “The economy certainly is not growing vigorously,” warned the paper’s financial reporter on July 18th,” Strike activity on behalf of sharply higher wages is intensifying. And the upward sweep of prices is continuing.” The article goes on, mentioning the telephone and copper strikes occurring simultaneously with the railroad. The three concurrent strikes were said to be in response to inflation and the increasing cost of living.

The RTD’s representation of the strike relied heavily on data, listing money lost and companies closed in response to the lack of transportation. Only one article referenced the average yearly pay of UTU members, $12,150, and no articles discussed possible figures for the money that workers could lose due to the changing policies. Nearly every article included figures for income lost by large companies. Within this discussion of loss, the coal industry played an important role and specific numbers were given: 210 closed mines in West Virginia, Virginia, Kentucky, and Ohio 3.5 million dollars lost in coal wages and over $500,000 lost for the United Mine Workers welfare and retirement fund. This was a useful and strategic move, which may have created strife among different unions and pitted rail workers against coal workers. These articles not only placed the two industries’ workers in opposition, but also functioned as a way of inciting anxiety among citizens who depended on coal for electricity. The RTD’s framing of the strike conveyed their anti-union sentiment by creating friction between groups of people and instilling a sense of fear for the loss of necessities and convenience.

Electricity was not the only concern for Richmonders, the RTD also raised fears regarding food and the potential for shortages. Near the strike’s end, on July 30th, an article noted that no food shortages had occurred thus far, however, that did not keep the RTD from stoking the fire. An article from July 18th, noted that the striking railroads carried 23 percent of the United States’ produce. Other articles discussed how grain and other food items were being stockpiled. Also targeted was the pinch felt by the agriculture industry, which the RTD reported on July 30th, would soon run out of livestock feed. This tactic, focusing on the availability of food and the possibility of shortages, was an emotional manipulation that did not stop with articles.

On August 1st, the RTD printed an editorial, “UTU v. the People” alongside the cartoon titled, Sleepwalker. This editorial placed the union in conflict with the citizens and explicitly presented anti-union opinions. One passage read,

On August 1st, the RTD printed an editorial, “UTU v. the People” alongside the cartoon titled, Sleepwalker. This editorial placed the union in conflict with the citizens and explicitly presented anti-union opinions. One passage read,

This strike does more than pit railroad labor against railroad management. It also pits railroad labor against the Richmond housewife, the Tazewell County coal miner, the Nebraska wheat farmer, the California vegetable grower, the Southern poultryman – and the Idaho lumberman. The shopper who watches supermarket prices soar because of the strike, the farmer who watches his summer’s work rot in the sun because of the strike and the non-railroad worker who finds himself idled— and probably broke– because of the strike are the real victims. In this dispute, it is a union of less than 200,000 railroad workers against the American people.

By creating victims and villains—the “American People” and the rail workers—this editorial made strikers into an un-American enemy. In addition, the RTD attempted to discredit the union by reproaching their demands, arguing that the strike lost credence because it was not focused on money, but instead on resisting the change to policies that the RTD deemed “archaic work rules that impair railroad efficiency.” The paper showed no restraint in expressing its opinion and did so with manipulative language, creating contention that may or may not have existed.

In the cartoon accompanying this editorial, the union is portrayed as violently holding up the nation’s economy, while demanding to be treated to a featherbed life of comfort. This cartoon visually represents the social divides the RTD had been encouraging throughout its coverage of the strike.

In the cartoon accompanying this editorial, the union is portrayed as violently holding up the nation’s economy, while demanding to be treated to a featherbed life of comfort. This cartoon visually represents the social divides the RTD had been encouraging throughout its coverage of the strike.

The paper printed two Southern Railway system advertisements on July 19th and August 1st. The first to appear showed a list of recent strikes listed along a railroad track. The second, a letter from a young boy to the president of the Southern Railroad, targeted readers’ emotions. Both included appeals to readers to write to their local government leaders about creating an Emergency Board to resolve the strike. Like the RTD’s articles and editorial, these ads appealed to the citizens with lines like this, “Alternative means of transportation can be costly. And who pays the cost? You—the consumer.” These ads sought to discredit the strike in the same way as the RTD editorial, by asserting that strikers could not tolerate rational efforts to “increase productivity.

The campaign against the UTU Railroad Strike was one of strategic emotional manipulation and demonstrated how anti-union attitudes prompted social divides. While the RTD’s emotional attack of the UTU was not motivated by an official endorsement for Nixon’s reelection, their anti-union beliefs aligned with their future endorsements of Republican presidential nominees from 1980 to 2012. The RTD’s anti-union rhetoric is full of patriotism, morality, and emotions, similar to that of the approaching storm of Conservatism.

For Further Reading:

Jefferson Cowie, Stayin‘ Alive: The 1970s and the Last Days of the Working Class. New Press, 2010.

Ken Fones-Wolf & Elizabeth A. Fones-Wolf, Struggle for the Soul of the Postwar South: White Evangelical Protestants and Operation Dixie. University of Illinois Press, 20

Image Credits Not From Exhibit:

Letter from Kyle Swanson, Aug. 2, 1971. Richmond Times-Dispatch.

How Many Rail Strikes Can You Put Up With?, July 19, 1971. Richmond Times-Dispatch.