“Come along with me

To my little corner of the world

Dream a little dream

In my little corner of the world”

— Anita Bryant, My Little Corner of the World

From the hidden little corners of gay bars and living rooms, the LGBTQ community began to emerge into the public eye in the 1970s. The decade between the Stonewall riots and the AIDS crisis brought powerful gains in visibility, acceptance, and civil rights for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender communities. Launched in large coastal cities like New York City and San Francisco, an evident emergence of the LGBTQ community appeared in rural towns and smaller cities across the country as well. In conservative Richmond, Virginia, the fight for gay and lesbian visibility was kickstarted in the 1970s, illustrating how the intersections of culture, politics, and institutions formed grassroots movements in the American South.

New and unprecedented depictions of gay and lesbian life in American mass culture helped to make the LGBTQ community visible as a cultural presence. In 1972, That Certain Summer, the first television movie to address homosexuality, debuted, as did the Academy-Award winning Cabaret, said to be one of the first movies to embrace homosexuality. This new LGBTQ presence existed not only in mass culture, but also on the streets of American cities. Commemorative marches of the Stonewall Riots began in 1970, starting with the Christopher Street Liberation Day parade in New York City and spreading to cities across the country, including Richmond, Virginia in 1979.

The increased visibility of the LGBTQ community resulted in significant social and political victories. In 1973, the American Psychiatric Association removed homosexuality from their list of mental disorders. A year later, Kathy Kozachenko became the first openly LGBTQ elected official, winning a seat on the Ann Arbor, Michigan City Council. The first federal gay rights bill addressing discrimination of sexual orientation was introduced in the U.S. House of Representatives on January 14, 1975. (The bill died in committee.) In a monumental ruling for transgender rights, professional tennis player and trans woman Renee Richards won a U.S. Supreme Court case allowing her to compete in the U.S. Open. When openly-gay Harvey Milk was elected as San Francisco’s city supervisor in 1978, he successfully passed a city-wide ordinance to prohibit anti-gay discrimination in housing or employment. San Francisco was at the forefront of emerging gay rights non-discrimination ordinances—in big metropolitan areas, such as Washington D.C. and Seattle, as well as in smaller cities and counties across the country.

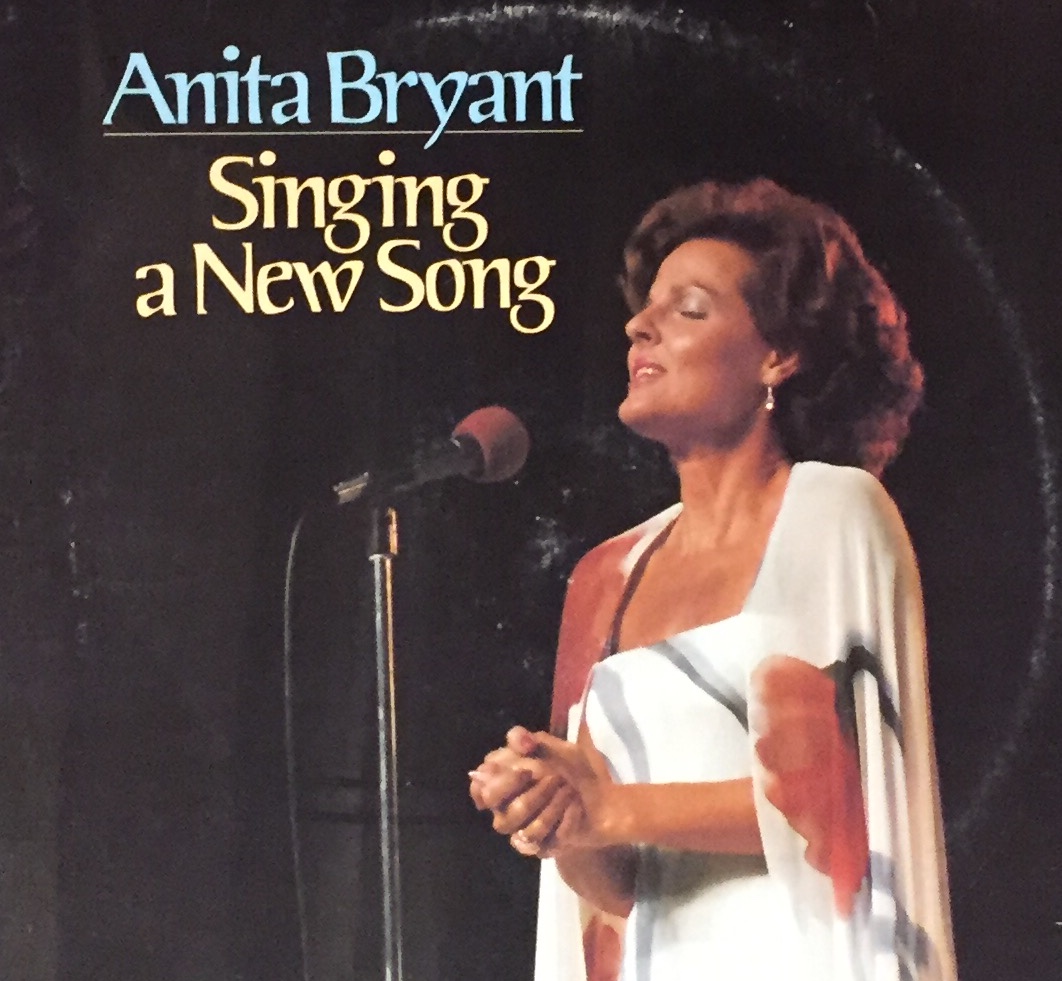

Yet, this progress also brought backlash. When Dade County, Florida passed its own gay rights ordinance in January 1977, the popular singer, Miami resident, and former beauty queen Anita Bryant began a campaign to repeal the ordinance, successfully gathering the signatures for a referendum in just six weeks. In her own words, the ordinance would:

…allow homosexuals to provide “role models” for the impressionable—that is, the right to tell all society, especially our youth, that homosexuality isn’t wrong, just “different.” This recruitment of our children is absolutely necessary for the survival and growth of homosexuality—for since homosexuals can not reproduce, they must recruit, must freshen their ranks.

Declaring this a campaign to “Save Our Children,” Bryant’s call for mass action marked the beginning of an organized opposition to the LGBTQ rights movement.

While calling for a return to “traditional” moral values, Bryant and the rising evangelical opposition to gay rights drew political rhetoric and tactics from the modern civil rights movements for black equality. The burgeoning anti-gay religious right framed their arguments in terms of the civil rights of parents to save their children from the homosexual influence. Historian Gillian Frank argues that this rhetoric signals that “conservative opposition to gay rights evolved alongside its opposition to African American civil rights.” The use of this civil rights rhetoric pitted the citizenship of parents directly against the citizenship of gay people, creating this dichotomy in order to force voters to choose one or the other.

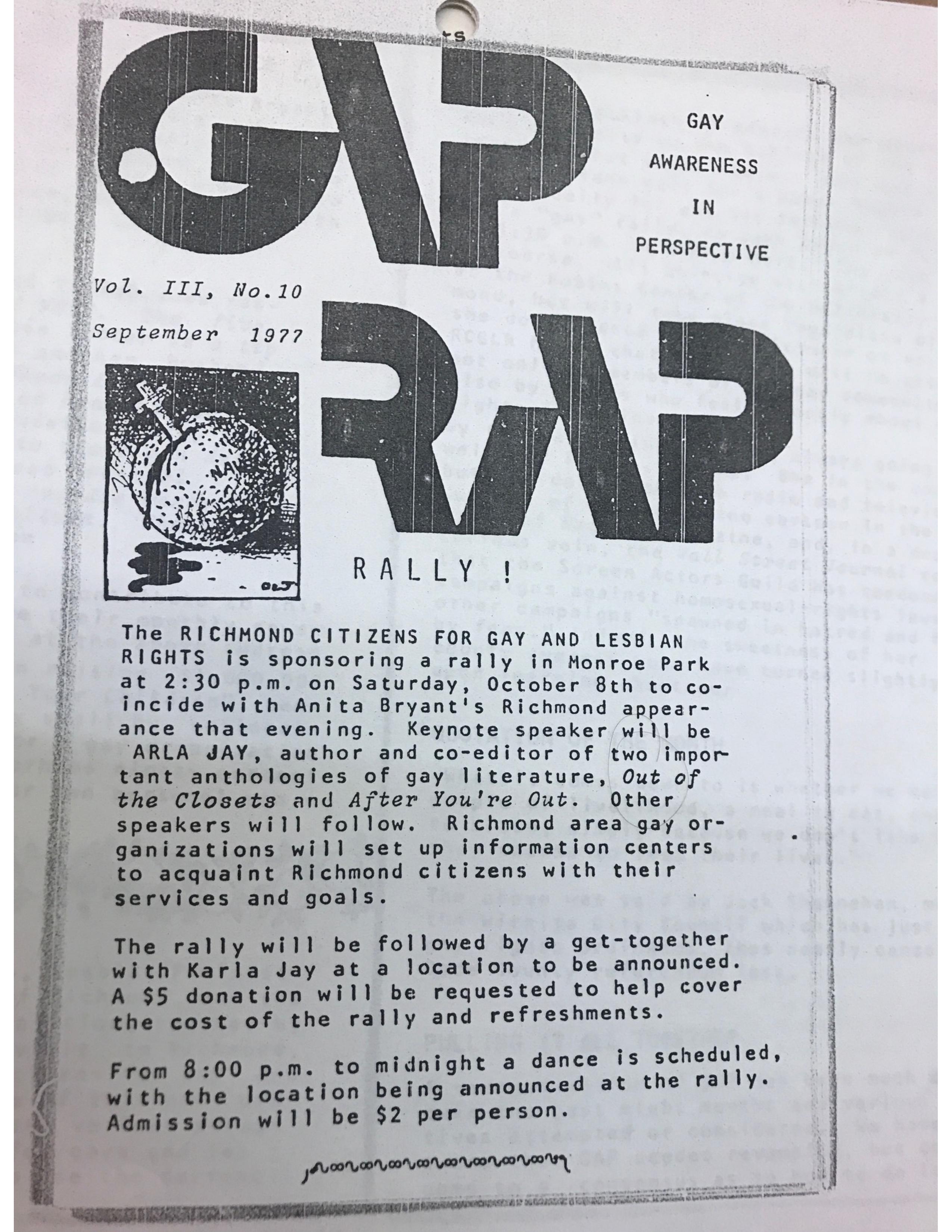

In Richmond, Virginia, the 1970s also marked a new era for LGBTQ activism. In 1974, Gay Awareness in Perspective (GAP), Richmond’s first formal gay organization, was founded. GAP published the first newsletter for Richmond gays and lesbians, titled the GAP Rap. Richmond also hosted its first pride parade—advertised as “Lesbian and Gay Pride Day—in June of 1979 in honor of the tenth anniversary of the Stonewall Riots.

On October 8, 1977, Anita Bryant was invited to perform at the University of Richmond’s Robins Center in an event sponsored by the University and the First Baptist Church. Richmond’s student newspaper, The Collegian, reported on October 6, 1977 that the invitation to Bryant had preceded her involvement in the anti-gay campaign. However, Bryant’s performance was well received at the University of Richmond. She gifted her memoir, The Anita Bryant Story, to the University, inscribed with a note: “To all my friends at the University of Richmond, especially to the wonderful president Bruce Heilman.” Amid backlash to her visit, she also published an editorial in The Collegian, stating “It is my understanding that the University of Richmond is a Christian college, teaching that homosexuality is a sin.”

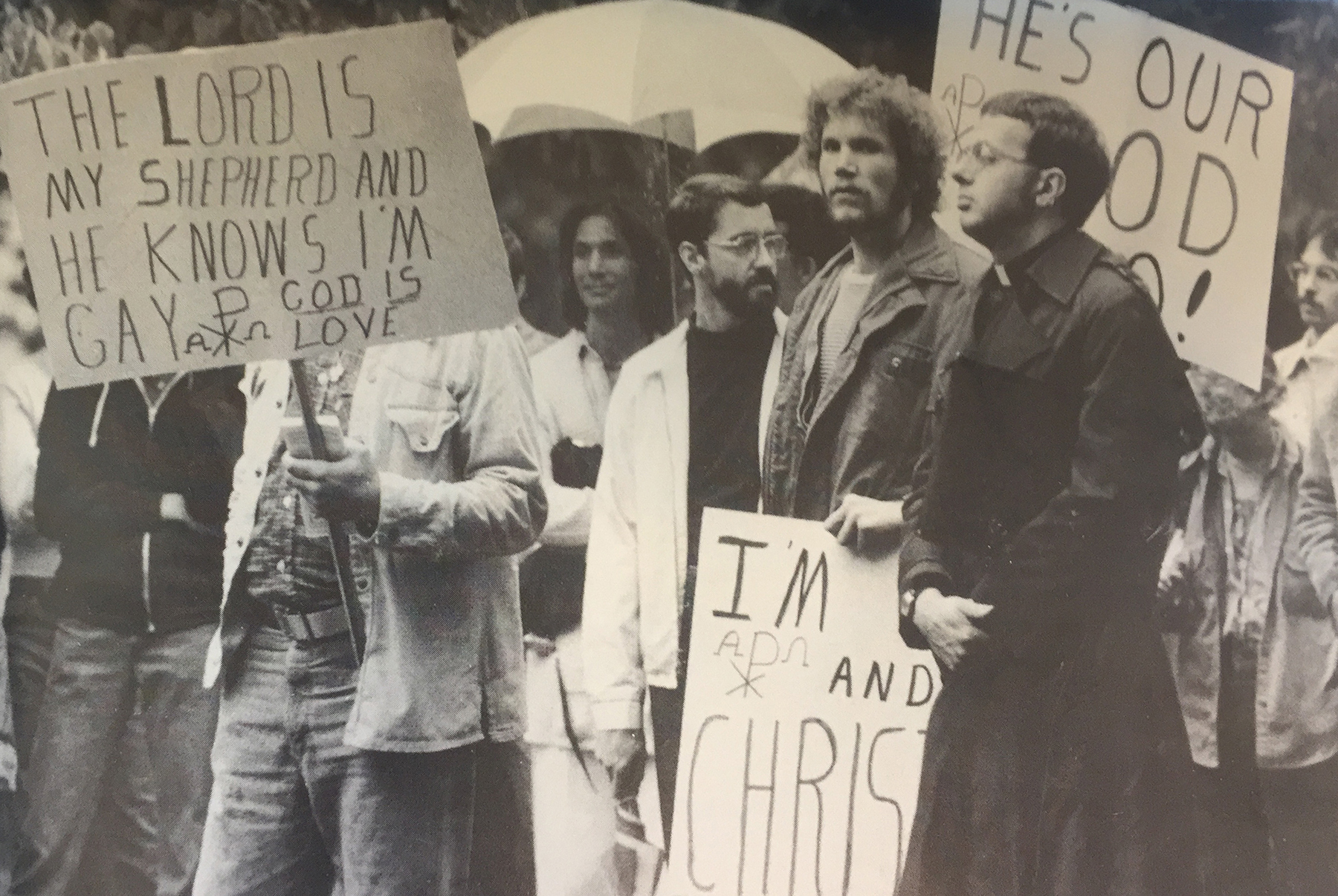

In response, local activists organized Richmond’s first gay and lesbian rights rally on the day of Bryant’s performance. The call to protest Bryant drew several hundred supporters to Monroe Park, celebrating the gay and lesbian community and protesting, to quote the GAP Rap, “Anita Bryant, anointed High Priestess of Homophobia.” The Monroe Park rally also sparked greater activism within the city’s LGBTQ community; two weeks after the protest, the Richmond Gay Rights Association was formed.

From San Francisco to Richmond, the 1970s shook the foundation of the LGBTQ rights movement. Creating both significant progress and a unified opposition, the 1970s ended with what scholar and activist Urvashi Vaid has described as “perhaps our biggest cultural success to date”: the first National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights in 1979. With 200,000 people attending, the grassroots-organized march capped off a decade marking the visible beginnings of a long fight ahead.

For Further Reading

Marschak, Beth, and Alex Lorch. Lesbian and Gay Richmond. Charleston, SC: Arcadia, 2008.

Vaid, Urvashi. Virtual Equality: The Mainstreaming of Gay and Lesbian Liberation. New York: Anchor Books, 1996.