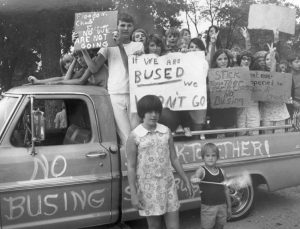

On August 26, 1970, a group of white elementary and middle-school students gathered on Richmond’s Southside and caravanned to Oregon Hill in an anti-busing motorcade. Spray painted with the words “No Busing,” They packed a pick-up truck, waving signs saying “If we are bussed, we won’t go!” and “What ever happened to freedom of choice?” The chanting children and their families defied a court order to desegregate Richmond Public Schools by busing students across neighborhood lines.

On August 26, 1970, a group of white elementary and middle-school students gathered on Richmond’s Southside and caravanned to Oregon Hill in an anti-busing motorcade. Spray painted with the words “No Busing,” They packed a pick-up truck, waving signs saying “If we are bussed, we won’t go!” and “What ever happened to freedom of choice?” The chanting children and their families defied a court order to desegregate Richmond Public Schools by busing students across neighborhood lines.

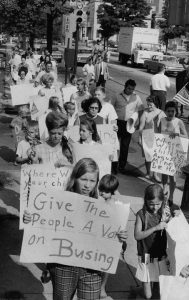

For many, the protests were about maintaining their rights to freedom and autonomy, questioning the constitutionality of the ruling’s provisions to move students across district lines without consent. Another demonstration along Franklin Street near Virginia Commonwealth University featured women and children marching together with signs that read “Give the people a vote on busing.” Already opposed to school integration efforts in general, the lack of say or vote in the busing decision angered Virginians even further, feeling as if the principles of majoritarian rule was being ignored and their right to autonomy suppressed. During a demonstration outside the Richmond Coliseum, a woman stands holding an American flag, and a man likened busing schoolchildren to Nazism and Soviet communism. For many, the impetus behind these busing efforts—to give children an equal chance at a decent public education—was completely lost.

Before the rise of the public school, schooling in early America was neither free, public, or widely available for white or black children. Formal education was reserved for the elites able to afford “dame schools” and private instructors. In the late eighteenth century, Thomas Jefferson’s proposal of a general education system strictly favored white males, with a limited amount of schooling available for females and absolutely none for enslaved of free-Black people. Later, Horace Mann’s principles spurred the start of the public school system.

Very few African Americans received any education at all until the Reconstruction era. Public schools established during this period were explicitly divided between black and white children. Such practices became codified into law when in 1896, the US Supreme Court upheld in Plessy v. Ferguson, the constitutionality of racial segregation in public facilities as long as they were “equal” in quality. More often than not, this was not the case. Many whites did not want blacks to become educated, fearing they would challenge white supremacy and compete for jobs. As a result, schools for African Americans received less financial support than did white schools. Students utilized worn and outdated textbooks handed down from white institutions. Buildings were often left in disrepair and teachers underpaid. Such conditions marked black Virginians with a stigma of inferiority and second-class citizenry.

The1950s brought about a series of lawsuits that ultimately led to the landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision to overturn separate but equal and integrate public schools. It called for a consolidation of white and black public school systems s. However, there was no timeline or follow-up to this demand. School divisions could begin this process with “all deliberate speed,” meaning at their own pace. This opened the avenue for a series of resistance movements across the country.

Virginia fought school integration as fiercely as any state of the former Confederacy. After the Brown decision, the commonwealth’s powerful senior Senator Harry Byrd Sr. called for “massive resistance” to the ruling. He promoted the “Southern Manifesto” opposing integrated schools and passed laws intended to maintain public school segregation by cutting off state funds to integrated schools and providing state tuition grants to students who wished to attend the school of their “choice.”

Despite massive resistance, Richmond’s public schools began integration in 1964. White Virginians responded by moving out to the neighboring suburbs of Henrico and Chesterfield counties in mass numbers. Between 1960 and 1975, the percentage of white students in Richmond plummeted from 4 to 21 percent, taking their support for public education along with them.

In spite of white resistance, efforts at integration persisted and the case Bradley v. Richmond School Board in 1970 brought about a limited citywide busing program to bring children together. That year, Richmond public schools were 70 percent black while those of the two counties were about 90 percent white. Because public schools are based on drawn attendance zones that reflect particular neighborhoods, students in Henrico and Chesterfield counties would have to be bused into Richmond in order to decrease the high percentage of black students in Richmond’s schools. That same year, the U.S Supreme Court approved busing across the country and families, from Boston to Los Angeles took to the streets. A wave of outrage led to demonstrations across Virginia for over two years, placing Richmond amongst the most defiant cities in the nation.

A key feature in these protests was the audience. These protests often presented white children as innocent victims of social engineering. In many of the photographs, children and young students are at the forefront. They were branded as targeted sufferers of unfair policies and purposefully used to gather sympathy from white politicians and representatives. White parents claimed their children would be exposed to danger, violence, and bad influences if bussed into predominantly black neighborhoods. For many, opposing this movement served as a scapegoat for their prejudiced views, cloaking their disdain for desegregation in flagrant anti-busing rhetoric.

These claims and protests were truly ironic, as black children and families were the true sufferers of unfair policies and unequal treatment. Rather than a suppression of rights, supporters of the busing movement viewed the Bradley decision as upholding the true promise of American freedom: the ability to receive a quality education no matter your zip code. For many black families, the busing movement was less about the intermixing of races than the expansion of educational opportunities.

Ultimately, the Richmond school-busing program failed. In June 1972, the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals overturned the decision. What remained were the lasting impacts of white flight. Support for public education plummeted, and schools only continued to deteriorate. In the ensuing 35 years, Richmond’s city schools went from being 57 percent white to 88 percent black. By, 2010 white students accounted for less than 9 percent of student enrollment. In 2015, three quarters of the city’s 23,987 registered students were on free or reduced lunch programs for impoverished families. As Chesterfield and Henrico County schools continue to grow, Richmond City schools face constant closure due to budget cuts and flat enrollment rates.

While school-busing efforts attempted to break down the barriers for African Americans to gain an equal education, achieving this ideal has never been easy or simple. Across the nation, busing plans faced steep decline in the 1980s, and today, no American city employs this technique. As such, the achievement gap between minority and white children is still alarming and policy makers, educators, and parents continue to debate this problem. In Richmond, schools are continuing their fight for equity. Schools and families alike hope meaningful integration is still a possibility, even 64 years later.

For Further Reading

Matthew F Delmont,. Why Busing Failed: Race, Media, and the National Resistance to School

Desegregation. University of California Press, 2016.

Robert A. Pratt, The Color of their Skin: Education and Race in Richmond, Virginia, 1954-89.

Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1993.

Clara. Silverstein, White Girl: a Story of School Desegregation. University Of Georgia Press, 2013.

Photo Credits

Richmond Times-Dispatch Collection, Valentine Richmond History Center