Commodity Money Basics

It is important to our overall understanding of economics that we take a look at key aspects of our economic origins. In this article, we will examine the basic theories and mechanics in commodity money, starting with defining some key terms. Commodity money is money made of some good that has intrinsic value. To break that down even further, money is commonly defined as something that serves as a medium of exchange, a store of value and a unit of account. Something has intrinsic value when it has value in itself. In other words, something has intrinsic value when the item itself has uses and people want it. This concept may be understood more easily when compared with its opposite, extrinsic value. This means that an item is representative of something of value, the way a check is representative of money in a bank account.

Throughout the early history of human economics intrinsic value was the only value considered for use or trade. This focus on intrinsic value went hand in hand with the economic system of early civilization that you’ve likely heard of; the barter system. In truth, the barter system was not used purely, as popular early economics education would have us believe. In fact, in his book “Debt: The First 5,000 Years,” David Graeber explains that systems of debt and credit were widely used because of the significant issues with the barter system. That said, this article will deal only with the barter system in relation to commodity money’s origin story because in many ways this basic system of debts and credit remained, while the issues of the barter system put in motion a shift in economic system.

During the barter system era it became clear that certain goods had qualities that made them convenient for wide use in transactions. Having intrinsic value is one of these qualities; durability, divisibility, transportability, and noncounterfeitability are the others. All of these qualities together make up the criteria for good commodity money. To understand more clearly how the mechanics of commodity money works in practice, it is helpful to start by looking a little deeper into where commodity money developed: the barter system.

The barter system, where the goods one has or can produce is what one can exchange for some item of want or need, has significant flaws. For one thing, there needs to be a “double coincidence of wants” for an exchange to occur. This means that two individuals have goods that they are willing to exchange and that the other wants. In practice, facilitating an exchange that satisfied both parties could be prohibitively difficult. The difficulty of coordinating each transaction enormously complicates and slows down an economy. While the barter system was in use certain goods that would eventually be commodity money would be used to make transactions easier. Imagine one person who makes clothes and needs work on his roof. But the roofer doesn’t need any new clothes. The first man could find a trade for some universally valued good, such as a staple crop, he could then trade that to the man who worked on roofs for his service, and everyone would get a fair value for their work. Through this process, certain goods emerged that had many of the qualities of commodity money and they would essentially be used as such.

These goods have certain qualities that make them desirable and expedient for exchange. These same qualities are true of all good commodity money as stated previously: durability, divisibility, transportability, and noncounterfeitability, in addition to having intrinsic value. Examples of early forms of commodity money, such as crops, herbs and spices, certain stones, shells, and precious metals (which had intrinsic value for their decorative nature), lacked some of the essential qualities of good commodity money. For instance, most crops or spices were not durable and were difficult to transport in large quantities. The quantities themselves would usually be measured in some unit of weight, which itself could be purposefully altered for their own ends by less than moral traders who would essentially be counterfeiting. The takeaway here is each of these forms of commodity money had significant flaws. As a next step, the economic authorities of those times would take would aim to reduce those flaws as much as possible. To accomplish this goal, more established political economies looked towards the standardization of the most commonly used commodity money, specie, which is another name for precious metals turned into coin.

The most significant issue with precious metal as commodity money (specie) is its durability and noncounterfeitability. Gold and silver, the most valuable and most commonly used precious metals for commodity money were also the softest. For this reason coins made only of these metals would wear down quickly over time, losing some of its value (tied to its weight, but more on that later) and its stamp, which was used on each coin to differentiate specie from bullion (raw gold or silver) and increase the difficulty of counterfeiting. Some form of specie has been in use for thousands of years, though it has fallen out of popular use during the last few centuries.

Mechanics

The mechanics of early commodity money systems varied somewhat because the medium of exchange differed by era and location. The medium of exchange is the most important aspect of commodity money. Depending on the medium of exchange, the transfer and storage of value might be exceedingly easy or difficult. Commodity money, importantly, has two types of value: One is value for use and the other is value for exchange. Value in use means that the good has desirability of its own accord, it creates demand because people need or want it very much. Value in exchange lies in how easily the commodity money could be traded for other goods, which themselves have more value in use. A good example is a unit of exchange that the Sumerians used; a certain weight of barley was called a Shekel. Barley might have value in use for some, but for others, it had value almost exclusively in exchange; meaning an individual would rather exchange one Shekel for another item with the same value in exchange, but would have even higher value in use for the individual. Note that the value in exchange is also related to modern ideas of supply and demand. If a good is too readily available, even if its value of use is high, its value in exchange would drop.

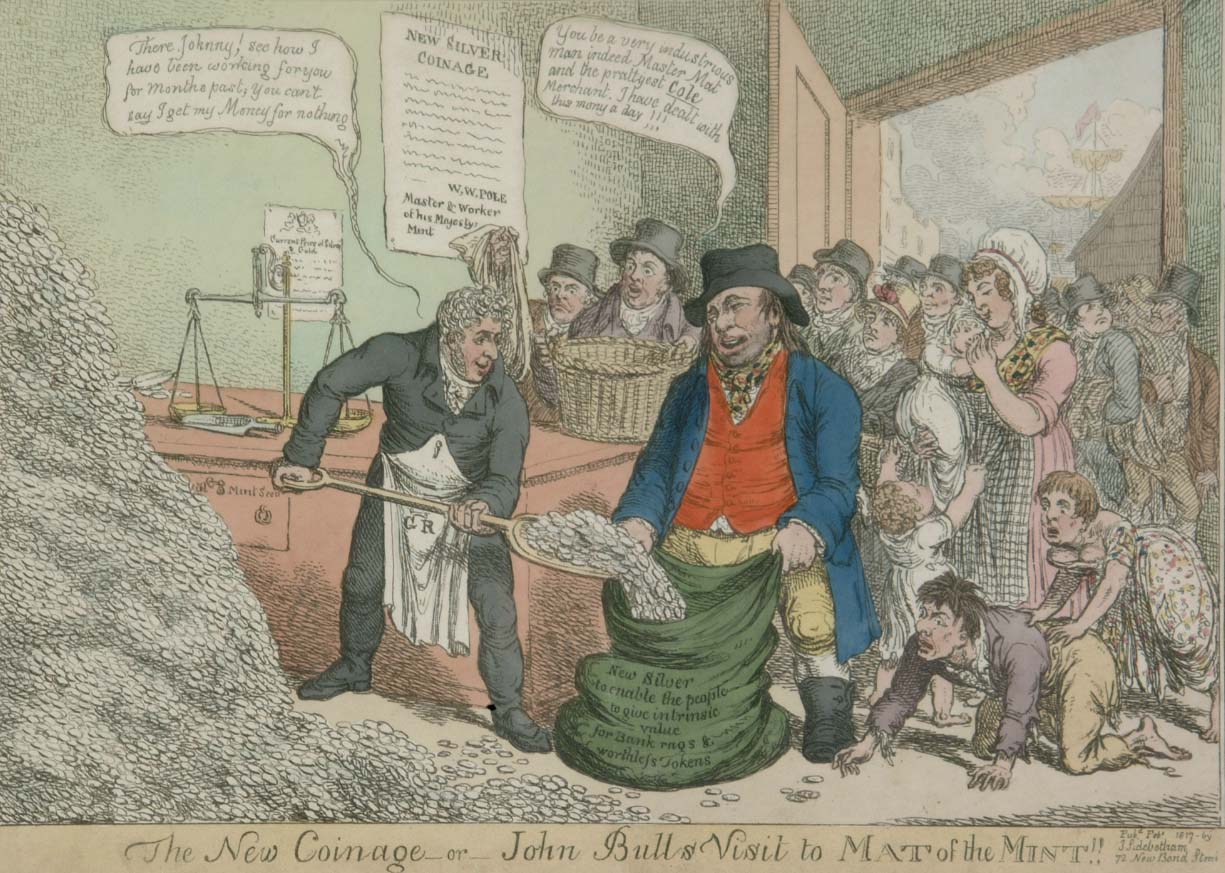

With specie, both the supply and demand as well as the physical makeup of the coin were important to understanding its value. The value in exchange of specie is related to the nominal value and the price of gold and silver as well as to the amount of gold or silver that is in each coin. The nominal value of specie is the value stamped on the face of the coin by the mint (the body that turned bullion into specie). The amount of gold and silver in each coin is a function of its weight and fineness. The weight of a coin is as it sounds, just what it weighs, but the fineness is the percentage of purity of the precious metal in the coin. Because silver and gold are soft metals and not very durable, every coin had to be mixed with another more durable metal. How much a coin is diluted with a harder metal determines its fineness and therefore affects its value in exchange. In Britain in the 1690s, for example, there was a pivotal economic crisis, which would later be called “The Great Recoinage,” some of our greatest thinkers have argued the advantages of debasement, which is the process of decreasing the value of commodity money.

Debasement

In the case of metal coinage, debasement is done by decreasing the amount of the precious metal in a coin, thus decreasing its fineness or overall weight. This would not affect the nominal value of the coin, but instead has the effect of inflation. The prices of goods would reflect that the value of each coin, and therefore the value of each nominal unit, had decreased. This would help raise funds for the government, as precious metals brought to the mint (where the government at the time took a fee to turn bullion to specie) could go further than before. The increased amount of coin would increase the liquidity of the quantity of money (total money circulating in the economy). Liquidity, money being available in an easily usable form, was a significant goal of debasement during a time when many economies didn’t have a satisfactory level of specie in circulation.

Because of the benefits, especially to the government who had to the power to choose if or when to debase, debasement wasn’t uncommon. Some, like William Lowndes, wrote in support of it, thinking that nominal value was more important than the price of silver, and that debasement would bring more bullion to the mint than was already coming in. Others, like John Locke, one of the greatest thinkers of his time, argued fiercely against it. In his opinion, the intrinsic value of the coin was more important than the nominal value, and by this way of thinking, changing the nominal value wouldn’t help the economy the way Lowndes believed. Locke also defended the “sterling standard”, which was the standard ratio at which silver was combined with copper (or other more durable metals) to increase durability. Clipping of coinage, the act of taking some of the precious metal from a coin, had become rampant with the soft, low durability coinage that was in place. Having the “sterling standard” for the fineness of silver and copper coinage helped curb this, according to Locke. Still problems like clipping, counterfeiting and lack of liquidity would persist and new forms of money would come about by necessity.

Transition From Commodity Money

As previously suggested, having enough precious metal for an economy to run smoothly on specie was not easy. In fact, it was the key issue of commodity money. Importing merchants took specie away from the local economy, decreasing liquidity as locals spent their specie on imports. In essence, an unfavorable balance of trade, with imports greater than exports (which bring specie back into the economy) would over time deplete the liquidity of the economy in a region. This flow of specie between economies is called the David Hume Price-Specie flow and led to the question: How would the necessary payments be made to keep an economy running without coinage? This was asked by many during the 17th and 18th centuries. Eventually, with significant difficulty, the answer emerged in paper “fiat money”. A Conversation Between Rich and Plowman explained this shift well: “[The issue is] not whether paper money be as good as silver or gold, but whether it be better than no money” (2). As with all transitions on such a large scale, the shift from commodity to fiat money didn’t happen all at once, but now in our modern times fiat money and other more advanced monetary tools dominate.

A quick video showing how one modern scholar sees the importance of commodity money: